I feel compelled to reflect on the golden era of Kenyan fiction—the vibrant 1970s. When you consider Kenyan literature in the 1970s, six names come to mind: Meja Mwangi, Sam Kahiga, Mwangi Ruheni, Charles Mangua, David Maillu, and Grace Ogot. I hasten to add Asenath Bole Odaga and Marjorie Oludhe McGoye. They were writers for the everyday Kenyan, champions of the “tell it as it is” spirit and, at times, of pure “art for art’s sake.” You can feel, line by line, that they enjoyed themselves in the act of creation. They told our stories boldly, airing our dirty linen without shame. They wrote of prostitutes and rowdy barroom banter, of hard-drinking hustlers and criminals in their prime, of the underbelly that both scandalized and defined us. They made us laugh at our own absurdities while capturing the pulse of the age—leaving behind works that still stand as milestones in Kenya’s literary history.

The 1970s were a transformative period for Kenyan literature as the country’s writers began to carve out a unique identity for their works in the literary boom as they sought to reflect the times and entertain the young nation. The era was pivotal for African literature as it marked the rise of the African novel following the success of the African Writers Series (AWS), one of the most important publishing initiatives in African literary history launched in 1962 by Heinemann Educational Books in London. It was initiated by Alan Hill, Heinemann’s publishing director with Chinua Achebe as the first general editor. AWS had the vision of making African literature widely available—both across Africa and internationally. It led to the rise of the African novel across the continent, of course, and in Kenya any publishers supported the works by local authors in both creative and educational spheres. These were East African Publishing House (EAPH) on Kijabe Street, Heinemann Educational Books, Oxford University Press, Macmillan Publishers, Kenya Literature Bureau (KLB), and Longman Kenya. These were the publishers of the stories that rattled us awake from the slumber of the darkness after the jolt of post-colonial rennaissance. They were our refuge in a world of sudden jolting newness as Kenyan struggled with nationalism. The pioneering Kenyan writers were published at East African Publishing House mostly—also in part as African Writers Series. Later Longman and Macmillan saw the value in the fiction market, and Longamn launched their popular Spear Series which emerged as a pivotal platform, publishing a wide range of Kenyan authors who explored the social, cultural, and political landscapes of a post-independence nation. David Maillu early on chose the independent publishing path and launched Comb Books in the early 1970s to provide alternative platform for publishing kenyan stories, especially works that were unconventional and not easily accepted by mainstream publishers at the time. His goal was to offer affordable, accessible, and relatable books that spoke directly to ordinary Kenyans.

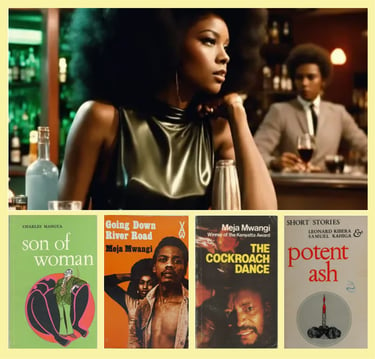

Charles Mangua may have been the forerunner. His literary career, though brief, left a significant mark on Kenyan literature with his two groundbreaking novels: Son of Woman (1971) and A Tail in the Mouth (1972). Both works, published by East African Publishing House, showcased Mangua’s sharp wit, bold storytelling, and his unapologetic exploration of gritty urban life in post-independence Kenya. In fact his books were very readable and gained popularity with young educated and unsophisticated Nairobians, mostly high school and university students of the 1970s. Mangua’s ability to blend humor, satire, and social commentary in a way that appealed to everyday readers continues to earn him a place in Kenya’s literary history, even though his career as an author was short-lived.

Mangua’s debut novel, Son of Woman, is a bold and unflinching tale that chronicles the life of Dodge Kiunyu, a streetwise hustler beating through the chaos and moral complexities of Nairobi. The novel explores themes of survival, corruption, and societal hypocrisy, offering a raw and honest portrayal of urban struggles. Dodge’s life unfolds in the shadow of his mother’s misfortunes as a single mother, and his journey is marked by rebellion, amorality, and resilience. The book resonated deeply with readers, particularly young urban Kenyans who could relate to Dodge’s story, and its irreverent style and humor made it an instant hit. However, its focus on controversial themes, including sexuality and crime, kept it at arm’s length from academic circles.

Mangua’s second novel, A Tail in the Mouth, continued his exploration of urban life but with a sharper critique of social issues like greed, corruption, and the moral decay of Kenyan society. While the novel displayed the same satirical edge and vibrant characters as Son of Woman, it didn’t achieve the same level of popularity. Nevertheless, it solidified Mangua’s reputation as a writer unafraid to tackle the uncomfortable truths of postcolonial Kenya. Despite the success of Son of Woman, his literary career was fleeting. After publishing his two novels, he largely retreated from the literary scene, taken up by his long stint at the African Development Bank, leaving behind a sense of unfulfilled potential. His works, however, remain significant for their pioneering role in urban Kenyan fiction, breaking away from the rural themes dominant in East African literature at the time.

Mangua inspired a new generation of talented writers who began to write about the rise of the drinking culture stemming from Nairobi's rapid growth and urbanization during the colonial era. The challenge of post-colonial nationhood had brough opportunity and hardship. Bars, clubs and drinking spots floursihed in the city in areas like River Road which was notorious for it mix of nightlife, liquour joints and this perpetuated the influx of sex workers. Prostitution, alongside squalor brought about by poor urban planning and infrastructure, was another widespread phenomenon, brought about by growing pupulation and mobility of workers. Writers normally reflect the times: Kenyan writers wrote about raunchy barroom scenes and cheap flesh peddlers. Writers like David Maillu, who was known for his controversial and widely read After 4:30 and My Dear Bottle, books that challenged societal taboos with his explorations of urban decadence, alcoholism, and sexuality.

Another writer publishing with East African Publishing House and coming close in the heels of Mangua was Mwangi Ruheni. A pseudonym for Dr. Nicholas Muraguri, he too was a master of urban narratives. Starting with What A life (1972), he prolifically rolled out his books—Future Leaders (1973), What A Husband (1974) The Mystery Smugglers (1975), The Minister’s Daughter (1975), The Love Root (1976) His books, the outsatnding one being The Minister’s Daughter and What a Life!, portrayed the challenges of life in Nairobi with humor and satire. His storytelling resonated with readers navigating the city’s chaos, from the struggles of the working class to the excesses of the elite. Like Charles Mangua, his works brought raw, unapologetic accounts of urban survival, exposing the underbelly of Nairobi’s streets with wit and candor. Mwangi, is in retirement, aged 90. Daily Nation describes him as “an extremely private and reticent man who is averse to giving interviews, has left an indelible mark on Kenya’s literary scene.”

The same paper called Meja Mwangi “a reclusive writer with a mighty pen”. It seems like great writing and publicity are strange bedfellows because real fiction writers are actually artists who don’t need public approval and publicity. Throughout history, some of the greatest writers have been known as much for their brilliance as for their reclusiveness. These authors shun the spotlight, avoiding interviews, public appearances, and even interactions with their readers. For many, this self-imposed isolation is a deliberate choice—an effort to focus solely on their craft or to shield themselves from the pressures of fame. Their mystique often adds to their appeal, making their works even more fascinating. Good examples are J.D. Salinger, Harper Lee, Emily Dickinson, Cormac McCarthy, and Kazuo Ishiguro. Reasons for reclusiveness are 1. Focus on Craft: Many reclusive writers believe that fame and publicity distract from the creative process. By avoiding the spotlight, they can devote themselves entirely to their work. 2. Personality and Preference: Some writers are introverts who find public attention overwhelming or even debilitating. 3. Preservation of Mystique: For some, like Elena Ferrante or Thomas Pynchon, anonymity becomes a way to let the work speak for itself, free of the author's personal baggage. 4. Protecting Privacy: Fame can come at the cost of personal life. Writers like Harper Lee or J.D. Salinger may have chosen reclusiveness to shield themselves from intrusive media attention. McCarthy believed that a writer's work should speak for itself and saw no value in self-promotion. The mighty James Hadley Chase never gave a single interview during the nearly five decades he wrote, from 1939 till 1984. Not a single one; he retreated to his Swiss villa and let his publishers and readers do the work.

Similarly, Meja Mwangi is famously reclusive and has avoided publicity throughout his life. He rarely gives interviews, seldom makes public appearances, is absent in social media, and is known to shy away from the literary limelight. In the 1970s literature, he emerged as the superstar of the pack. To date he remains to be one of Kenya’s most influential and prolific authors, often celebrated for his vivid storytelling, incisive social commentary, and ability to capture the pulse of everyday life in post-independence Kenya. Emerging in the 1970s, Mwangi’s works brought a new energy to African literature, shifting attention from rural themes to the complexities of urban life and the struggles of ordinary people. With a sharp eye for detail, a deep sense of humor, and a commitment to portraying the truth of his society, Mwangi has cemented his place as one of Kenya’s greatest literary voices.

Born in Nanyuki in 1948, Meja Mwangi grew up during a tumultuous period in Kenya’s history, as the country fought for independence from British colonial rule. This background deeply influenced his writing, particularly his early works, which reflect the socio-political upheavals of the time. He did A-level science and studied filmography briefly before venturing into creative writing. His debut novel, Kill Me Quick (1973), introduced readers to his gritty style and penchant for exploring the lives of the marginalized. It won the prestigious Jomo Kenyatta Prize for Literature, signaling the arrival of a bold new voice in Kenyan fiction.

He had initially started working with Heinemann Educational Publishers, who published Kill Me Quick (1973) and Carcase For Hounds (1974) a gripping tale of Mau Mau action story. In 1975, he moved briefly to EAPH, who published A Taste Of Death, his other Mau Mau action story that might have been inspired by real events and the main character, General Haraka, was obvioulsy casted to do what Mwangi wanted Field Marshal Dedan Kiamthi to do.

In 1976, Heinemann issued Going Down River Road, another of his widely acclaimed novels; one which was read by novelist Ngugi wa Thiong'o in detention. The story revolves around Ben, a former soldier, and Ochola, his friend and colleague, as they push through the challenges of survival in a city marked by exploitation and broken dreams. The novel’s raw realism, combined with Mwangi’s ability to create deeply empathetic characters, makes it a landmark in Kenyan literature.

Mwangi’s most famous works often explore the harsh realities of life in urban Kenya, touching on issues like poverty, corruption, inequality, and the resilience of the human spirit. In 1979 novel, he moved to Longman and launched The Cockroach Dance, which is considered a masterpiece of urban fiction. In it, Mwangi paints a vivid and satirical picture of Nairobi’s urban decay and the struggles of its lower-class residents.

His later works such as Bread Of Sorrow (1987), Weapon of Hunger (1989), and The Return of Shaka (1989) showcase his evolution as a writer, shifting from the gritty urban realism to more varied themes of international proportions, inluding historical refkection, and humanitarian issues.

But in the 1990s, Mwangi appeared to have slowed down and "matured up"and confronted issues that affect lives of people and culture, and he functioned as a writer calling for peace, awareness, compassion and action. Striving for the Wind (1990) explores the clash between tradition and modernity in rural Kenya while The Last Plague (2000) addresses the devastating effects of HIV/AIDS epidemic on Kenyan rural communities, dealing with fear, stigma, and ignorance sorrounding the disease, as well as the social and cultural dynamics that perpetated its spread. Throughout his career, Mwangi has demonstrated an uncanny ability to adapt his themes and settings, offering a diverse body of work that reflects the multifaceted nature of Kenyan society. What sets him apart is his ability to combine humor, satire, and pathos to create stories that resonate deeply with readers. His language is simple yet evocative, allowing him to reach a wide audience while still addressing complex issues. Mwangi’s focus on the everyday struggles of ordinary people—laborers, low level office workers, goons, drifters, hustlers, prostitutes—marked a departure from the grand, sweeping narratives of earlier African writers, carving out a unique space for him in the literary world.

Despite his international acclaim, Mwangi remains a somewhat underappreciated figure in Kenya, a reality that mirrors the themes of neglect and marginalization that permeate his works. His contributions to African literature are undeniable. His novels continue to serve as a lens through which readers can understand the social and economic challenges of Kenya’s urban centers, as well as the resilience and humanity of its people.

As one of Kenya’s literary giants, Mwangi’s work challenges, entertains, and inspires, and his voice remains as relevant today as it was when he first burst onto the scene. Whether you are revisiting The Cockroach Dance or discovering Going Down River Road for the first time, Mwangi’s stories remain timeless chronicles of life, struggle, and survival in Kenya.

Leonard Kibera and Samuel Kahiga, brothers and literary pioneers, co-authored Potent Ash, a collection of short stories published by East African Publishing House in the early 1970s. The book captured the complexities of a society grappling with modernity while still rooted in tradition. Together, the two brothers represented a generation of writers deeply concerned with the human condition and the shifting dynamics of post-independence Kenya. Of the two, Sam was the outstanding one; perhaps the talented one. He graduated in 1970 from the University of Nairobi's Faculty of Architecture, Design, and Development. But he was a creative soul caught between his passions for writing and music. Born in August 1946, he came of age during the tumultuous final years of colonial Kenya—a time defined by violent conflict, profound social and cultural upheaval, and the mixed opportunities brought by Christianity and Westernization. This dynamic period profoundly influenced his artistic vision and storytelling. He went on to cement his place in Kenyan literature with novels like Dedan Kimathi: The Real Story, The Girl From Abroad, Lovers In the Sky. His 1979 novel When the Stars Are Scattered, remains sweetly entertaining and memorable novel set in Mombasa; an exploration of love, loss, and societal change. Like all the others, he remained active throughout the 1980s and cut a niche for himself as a prolific short story writer. His short stories were frequently published by magazine such as True Love, Drum, Viva and Men Only. Alive and in retirement, Sam remains to be properly recognized and his place secured his place as the multi-talented, most versatile and prolific artists of post-independent Kenya. He is an author, painter, cartoonist, film maker and music composer—in one word, an artist.

What’s remarkable about Mwangi Ruheni’s and Sam Kahiga's fiction is that, much like their contemporary Meja Mwangi, they approached writing with enthusiasm and creativity despite the former being a professional scientist and the latter being an architect with no formal literary background. Unlike the works of Ngugi wa Thiong’o and Meja Mwangi, Ruheni’s and Kahiga's books were not widely celebrated in academic circles. However, they resonated with readers for their humor, wit, and relatable depiction of everyday Kenyan life, carving out a unique space in the country’s literary landscape. The same can be said for Charles Mangua, the banker caused a stir with the groundbreaking humor novels.

Other notable authors of the era included Henry Ole Kulet, whose works like Is It Possible? and To Become a Man focused on the tensions between pastoralist traditions and the pressures of modernization. Then there was Mwangi Gicheru wrote the lovable Across The Bridge and John Kiriamiti who penned the popular My Life In crime. Meanwhile, playwrights like John Ruganda, though more prominent in drama, contributed to the intellectual discourse of the time with works such as The Burdens and Black Mamba, which examined issues of power, oppression, and societal decay.

The 1970s also saw the rise of female writers like Grace Ogot, Marjorie Oludhe McGoye, Asenath Bole Odaga, Micere Githae Mugo, and Rebecca Njau, who brought fresh perspectives to Kenyan literature. Ogot’s The Promised Land and Land Without Thunder highlighted the lives of rural communities, blending oral traditions with written storytelling to explore themes of displacement and cultural identity. Rebecca Njau’s Ripples in the Pool tackled the struggles of women in a patriarchal society, offering one of the earliest feminist critiques in East African literature. Both writers added depth to the literary canon, showcasing the diverse experiences of Kenyan society.

The themes represented by these writers were as diverse as the authors themselves. Urban struggles, exemplified by the works of Mwangi Ruheni and Charles Mangua, captured the gritty realities of life in Nairobi. The tension between tradition and modernity was a recurring motif in the works of Grace Ogot, Rebecca Njau, and Henry Ole Kulet, as they grappled with the cultural shifts brought about by independence. Disillusionment with post-independence governance was another dominant theme, with authors like Meja Mwangi, Charles Mangua, Mwangi Ruheni and Sam Kahiga critiquing the unfulfilled promises of freedom.

Social satire and humor also found a place in the works of writers like David Maillu, whose provocative narratives offered biting commentary on Kenyan society. At the same time, female authors such as Ogot and Njau provided a much-needed feminist lens, addressing issues of gender dynamics and the roles of women in a rapidly changing world.

The Longman’s Spear Series, alongside other publishers like East African Publishing House, played a crucial role in nurturing this vibrant literary scene. These platforms not only gave writers a voice but also fostered a literary culture that reflected the complexities of Kenyan society. However, despite their significant contributions, many of these authors—particularly Meja Mwangi, Mwangi Ruheni and Sam Kahiga—have faded into obscurity, their works often overlooked in contemporary discourse. These men of letters, now in retiremnt or semi-retirement, are very much alive and active, though.

Rediscovering these writers is essential as their stories remain deeply relevant. They captured the pulse of a nation in transition, offering timeless reflections on identity, inequality, corruption, and hard life of the post-Independent Kenya using romantic tones. The enduring themes and vivid narratives of these authors remind us of the richness of Kenyan literature and its vital role in documenting the country’s history, challenges, and aspirations.

Reliving the Golden Era of Kenyan Fiction: Revisiting the Pioneers of the 1970s

J U N E 2 0 2 5

Bio

I'm Okang’a Ooko—a novelist and senior book designer with deep roots in publishing, storytelling, and design. I specialize in helping publishers and agents deliver polished, compelling books that resonate with their markets. Whether you’re producing high-volume titles or championing a first-time author, my design solutions ensure your books look as powerful as the stories they tell, captivating readers, and reflecting professional quality from cover to final page. As an author, my novels explore history, politics, culture, music, love, and identity—told through emotionally rich, character-driven narratives that captures nostalgia, societal conflict, and the personal struggles of those facing change and disconnection. Read more »

Ready to transform your story into something unforgettable? Okang'a Ooko specializes in end-to-end creative solutions for authors, publishers, literary agents, and storytellers. Whether you're crafting your first novel, launching a brand, or building an author platform, he's here to guide you from concept to creation. Learn more »

With decades of experience in storytelling, publishing, and visual design expertise. Ooko helps you bring your book, brand, or message to life—beautifully, strategically.

Turn your vision into a lasting impression. Hire Okang'a Ooko »

Hire Okang'a Ooko

Connect With Me

© 2025. All rights reserved.

Terms and Conditions I Refund Policy I Privacy Policy